Yes, I'm an Owner

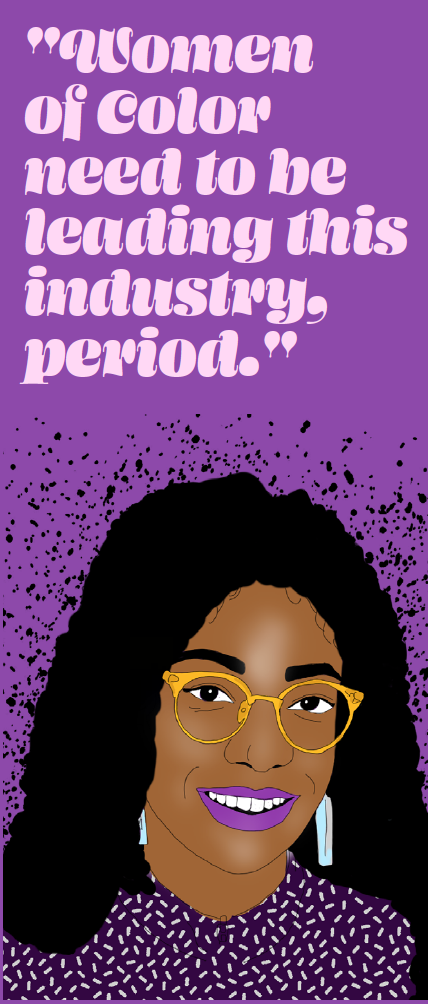

Bartender and owner at the cooperatively run Tanám, Kyisha Davenport shares her experiences and thoughts on women of color in hospitality, leadership and breaking into bartending as a Black women in Boston.

illustration: becki kozel

At Tanám in Somerville, Kyisha Davenport is a bartender and part of the ownership cooperative that runs the worker-owned restaurant in Union Square’s Bow Market. The food and cocktails tell the story of the Filipnx-American experience. Dining at the James Beard semifinalist spot had been interactive and communal. But since March, Tanám has been closed. Davenport, along with Chefs Ellie Tiglao and Sasha Coleman, is working on an online interactive dining series and planning for meal delivery. We spoke with Davenport on July 10th. She was in Brownsville, Brooklyn, where she grew up. People were flocking to the streets in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, Boston was in Phase 3, and, in many other parts of the country, the coronavirus was flaring up. Here’s what was on Davenport’s mind.

I was drawn to Boston for my career (and for that raw bar that one time, if I'm being honest). Since I was a teenager, I’ve worked primarily in hospitality. In 2012, as a bartender at the Barclays Center in Downtown Brooklyn, I got into labor organizing through the hospitality trade union UNITE HERE Local 100. As a shop steward—an elected on-the-job advocate—I connected with members along the East Coast. When the opportunity arose to organize with UNITE HERE Local 26 in Boston, I moved. Not long after I started, I split, pretty painfully, from the union. I've always struggled with the dynamics of political activism within hospitality. There’s deep work to be done in listening to Black women, protecting us, and respecting our leadership.

From the onset of Tanám, our leadership was constantly questioned by lenders, landlords, hospitality folks, and even guests. We had to explain ourselves day in and day out. "Yes, we are the managers. Yes, you are also speaking to the owners. Yes, all three of us are worker-owners. This is our business." These interactions happen in seconds, but when they happen multiple times in a day, it adds up.

[After splitting from the union,] a friend, who now owns and operates her own spot, HASH in Chicago, referred me to her then current workplace. I applied as a bartender, but was told there were only server openings—all good, work is work. But I kept watching nonblack folks come in and work or pick up shifts. Managers came and went. I asked to train on the bar, even to stage. I was never directly told no, but there would be a new white person promoted, hired, and so on. It's like that in the industry, and definitely in Boston. I kept looking, and finally landed a bar gig (two, actually). Those ended soon, too, because I spoke up about pay, tips sharing, menu development opportunities, and work safety. I found myself being moved off the bar and back onto the floor with less shifts, less income. Long after I left those jobs, old coworkers would reach out to tell me how brave I was, that I was right for speaking up, and how they admired me. Thank you, but when I needed you, where were you? The Strong Black Woman trope is alive and well in our business. We are expected to do the heavy lifting for everyone. And if we fall, well, "You go, girl! You got this!"

Death, Trapped: Spicy Black Pepper-infused Brandy, Roasted Pineapple, Calamansi, Ginger, MSG

Part of the lived experience of Black women are the seemingly insignificant, seemingly invisible slights. We call them microaggressions, but they're actually acceptably racist behaviors. When I bartended in the Seaport, I had very short hair, having shaved it clean off some months prior. At the heart of my culture is style, switching it up, and pulling from history and my imagination to create newness. One day, we went from short curly hair, to nearly waist-length waves. Overnight, I became that much more appealing! Guests and coworkers were so much nicer. I can still hear my manager's voice, with that mix of surprise, confusion, and… There should be a word for when you know you're being exoticized.

So that was work, and later that day, I went to an old job for a drink. It was still pretty early, moving but not busy. I grabbed a seat at the bar, my usual spot at the end. I waited, and waited. No greeting, no water. It takes a while to build a regular rapport at bars, and for Black people and people of color, I think it's essential to how we go out. I thought I was safe at this place where I’d worked before. In actuality, I found myself back at square one. Imagine that.

I literally pushed myself up onto the bar, nearly leaning over the drip rail, and called the bartender, "Hey, it's me. It's Kyi." And my guy, he says, "Kyi! I didn't recognize you!" Which is all well and good, but you only serve Black people you recognize? I'm a patron. Sitting right in your face. Ready to pay you. Why did I have to watch folks come in and be served before me? This kind of treatment is all too familiar to visibly Black and brown people.

The pandemic has forced white people to sit with themselves. Their mindset is that they’re not racist. But racism is not always an overt or violent action. White people had to think about the little things they do that have added up over time, and face their own racist behavior. It’s been useful for us. Folks reached out to see how we're doing and how they can help. It was a relief. It’s extremely exhausting to show up every day and face opposition for just showing up. We were putting out three menus from a 100-square foot kitchen every day—thoughtful, fresh, explorative menus. To do that every day and still be questioned about your skill level and your position, and be held to such a higher standard, is very frustrating. Women of Color are not trusted to lead. I’ve been in the hospitality industry since 2009, and we aren't afforded that straight out of the gate, like our white, male counterparts are. Women of Color need to be leading this industry, period.

Kyisha Davenport of tanam

When we learned of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd's murders, it was interesting to witness the response and the silence within the industry. I was surprised to read posts and articles about restaurants, organizations, and individuals that have no framework or legitimate reputation for being antiracist. I joke about it: "Did you all jump on the same Zoom or something?" If you’re just now acknowledging your whiteness and your complicity in systems that protect your whiteness, and if the day you posted this stuff is the beginning for you, then you've lived nearly all your life inflicting violence on Black people and people of color, without ever being held accountable. And then you go on to donate to these large national organizations, which is all well and good, but it’s also a cop out. The Black people you are now trying to support, are not somewhere far away. They are the very same Black people who sat at your bar, who you neglected to serve or took 30 minutes to drop a menu and a glass of water.

Boston is a diverse and deeply segregated place. There are conflicting histories behind the divisions—of solidarity, of rebellion. Black and brown people have been largely pushed to the margins of the city. Open a copy of Boston Magazine and look at the restaurant listings. There are more than 60 Black-owned restaurants in the greater Boston metro area, yet Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan—three distinct, majority-Black neighborhoods—get lumped into one paragraph, one blurb. It's lazy, it's racist, and it comes from white critics' fear of the spaces we create.

There are only eight Black-owned liquor licenses in the entire city (we hold a portion of one in Somerville). The mayor called for the issue of 15 liquor licenses to minority-owned businesses that can only be transferred to other minority-owned businesses. But when you think of the number of restaurants in Boston, we are still at a major deficit. Black food folks do not have equitable access to resources to create spaces where we can connect and build. Even our association with Black restaurants and businesses counts against us. When I moved to Boston, I was frustrated with being the only Black woman in the room. That mental and emotional strain is hard to quantify and put into words. I thought I would be like everyone else and just make drinks. That is just not possible. The ways in which we have to navigate this industry, a lot of folks wouldn't last. Trust.

I'm sure folks think I talk about race too much. To which I say, you're lucky that I do, and for free. Speaking on injustice to bring about justice is always something I've done, and nearly always at a financial, physical, or mental cost. There is no one group, institution, entity, that is not affected by racism. Intersectionality requires internal upheaval. It's hard work. It’s hard to have those conversations with yourself, your friends, your coworkers, your bosses, and to grapple with the fact that you did harm to people. It’s scary to have to unlearn something because it may not serve you. I understand why organizations, even those somewhat on the margins, still do harm. It’s hard to decenter yourself when all your life you've been so centered that you can't even fathom what goes on for everyone else—it’s the normality of whiteness.

If you’re a nonblack person or not a person of color, you can no longer talk without action. Feel your shame, then keep pushing. Hire and pay BIPOC equitably. When you screw up, apologize and make it right. Accept that you do not get to decide what right is. Allocate money for racial justice work in your budget. I and many BIPOC have found that when we start jobs, white people trip over themselves to welcome us. But any difference of opinion we may have on a practice or policy or how we've been treated, makes us a threat. And before long, we find yourself being cast out, our jobs become unbearable, our shifts cut, our erasure and blacklisting imminent.

Pandan Punch: Coconut-washed Tanduay Gold Rum, Roasted Pandan, Golden Falernum, Coconut Milk, Lime

Back in 2018, I remember introducing myself to a chef who was also opening a business in Bow Market. In short, he told me Tanám was a stupid concept and that we should come work for him when we inevitably failed. Can you imagine this white man speaking to me this way? What I resent is that two years ago I couldn’t have spoken about this. There was no support for it. We would’ve been labeled attention seekers instead of people who experienced racism in a supposedly progressive city. And even now, I don’t fully trust the industry's commitment to anti-racism. Check the instagram feeds. See how many pages have gone back to business as usual after posting their black square.

As a kid, playing restaurant was one of my favorite games (next to playing “Ricki Lake,” haha), but I never saw myself owning one. President? Sure. Rockstar? Yes. What drew me to Tanám, and what has always been the bedrock of my work, is collective benefit, cooperative economics, and socio-economic justice. Most importantly, if you want to make an impact, you need to redistribute wealth. There is no revolution without reparations. Hospitality is built off stolen labor—stolen lives, cultures, histories. Boston and Somerville have declared racism a public health emergency. Yet, I can't so much as get a meeting with the Somerville Arts Council to fundraise for QT/BIPOC artists. We know how to lead. We need you to financially contribute to the work we're already doing, or put us in front of the people who will. There are deep wounds that if neglected, will never heal. Unless we address the original ‘pandemic’ of our society, none of us stands much of a chance. Despite all this, I believe we just might be ready to heal.

HELP SUPPORT

Black Trans Women to the Front: Mercédes Donnell, @lawdhavemerci

Mercédes, aka Merci D., is a Dorchester-based artist, rapper, muse, creative, and leader. To support funding for her safe and healthy medical transition, go to the link above, and follow her work on Instagram. Merci D.’s debut release, “Red Line,” is available wherever you listen to music.

Boston Ujima Project, @ujimaboston

A cooperative business, arts, and investment ecosystem built by and for Boston’s working class Black community, Indigenous community, and all People of Color.

CERO (Cooperative Energy, Composting, Recycling, and Organics), @cero.coop

A cooperatively owned and operated commercial composting company based in Dorchester. Deeply rooted in Boston’s working class communities and communities of color, since 2012 CERO has led the way for community-based entrepreneurship and envisioning and developing Boston’s green economy.

Frugal Bookstore, @frugalbooks

A community bookstore located in Roxbury with a passion of promoting literacy among children, teens, and adults.

The Urban Grape, @urbangrape

The self-described first “progressive” wine shop. Supporters of educational opportunities for BIPOC in hospitality, Owners TJ and Hadley Douglas organize their wines by body, rather than region or grape varietal. You can find a selection of Black-owned producers, women winemakers, and biodynamic wines in store or on their website.

BarNoirBoston, @barnoirboston

A QT/BIPOC Arts Collective founded by Kyisha Davenport that addresses the public health emergency of racism through direct funding, action, and the leadership of QT/BIPOC artists. You can demonstrate your support through Cash App $negrohontas or Venmo @Kyi-Davenport. To discuss fundraising, grants, and other financial and non-financial resources, reach out directly to BarNoirBoston@gmail.com.